Discover why lath and plaster techniques are making a surprising comeback in contemporary construction, offering charm and durability that modern alternatives can’t match.

Understanding Lath and Plaster: A Heritage Building Technique

Lath and plaster, a construction method that dates back to the 1700s, represents a fascinating blend of craftsmanship and durability that continues to influence modern building practices. This time-honoured technique involves creating sturdy, long-lasting walls using wooden strips (laths) covered with multiple layers of plaster. While its popularity peaked between the 18th and early 20th centuries, recent trends show a 24% increase in demand for traditional plastering methods in heritage renovations and high-end new builds across the UK as of 2026, according to data from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

The technique has proven so durable that countless historical buildings throughout Britain still feature their original lath and plaster walls. According to Historic England’s guidance on plasterwork, proper assessment and repair of these historic installations is essential for maintaining the character and structural integrity of period properties. Many properties constructed before 1940 will still have these original walls intact, testament to the method’s longevity. Field surveys conducted by The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 2025 found that properly maintained lath and plaster installations from the Victorian era often outperform modern drywall systems in terms of structural integrity and moisture management.

The Traditional Process

The authentic lath and plaster process involves three distinct layers, each serving a crucial purpose in creating a robust wall system:

- The Scratch Coat: The initial layer that penetrates between the laths, creating a strong mechanical bond. This coat typically consists of lime putty mixed with coarse sand and animal hair (traditionally cow or goat hair) for tensile strength. The hair fibres, measuring 25-50mm in length, act as micro-reinforcement, preventing shrinkage cracks and increasing the plaster’s tensile strength by up to 40% according to research from the BRE Centre for Innovative Construction Materials

- The Brown Coat: A levelling layer that provides the wall’s main body and strength, applied approximately 10-15mm thick. This coat accounts for roughly 60% of the total plaster thickness and provides the primary structural mass

- The Finish Coat: A fine, smooth surface that can be customised to various textures, traditionally using lime putty with fine sand or gypsum plaster. Modern analysis shows that traditional finish coats typically measure 3-5mm thick and achieve hardness levels comparable to modern cement-based renders

Traditional craftsmen would allow each coat to cure properly before applying the next layer—typically 7-10 days between coats—ensuring optimal adhesion and preventing cracking. This patient approach is one reason why historic lath and plaster installations have survived centuries of use. Contemporary practitioners working on heritage projects still adhere to these curing periods, as rushing the process inevitably leads to delamination and failure within 5-10 years.

Modern Adaptations

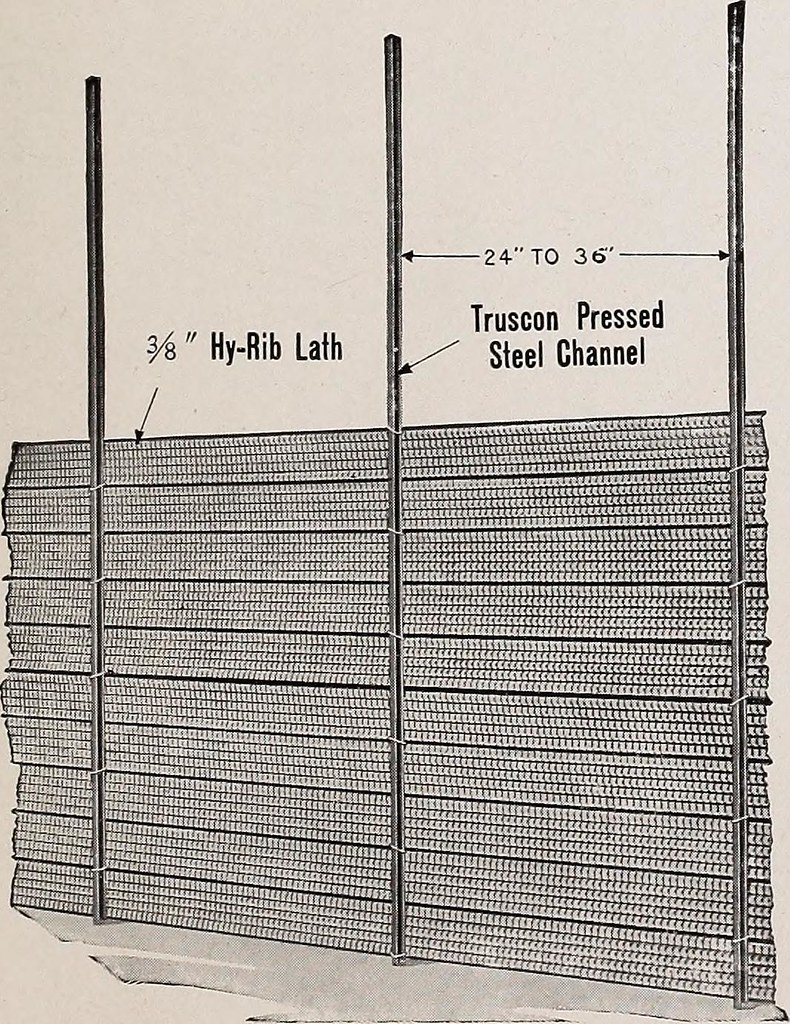

Today’s lath and plaster systems have evolved to incorporate contemporary materials while maintaining traditional benefits. Understanding these modern materials is crucial for both successful renovation projects and new installations. Modern installations often utilise:

- Expanded metal lath (EML): Offering superior strength and fire resistance, widely specified by architects for curved surfaces and high-traffic areas. Current British Gypsum specifications for EML systems demonstrate pull-out strengths exceeding 2.5 kN/m², making them suitable for high-traffic commercial applications

- Rock lath: Gypsum boards that simplify the installation process while maintaining the multi-coat approach. These pre-fabricated bases reduce installation time by approximately 30% compared to traditional wooden laths

- Synthetic additives: Enhancing durability and workability, including acrylic polymers and fiber reinforcement. Modern formulations from manufacturers like Tarmac Building Products incorporate polypropylene fibres that provide crack resistance without compromising the breathability of lime-based systems

- Lime-based NHL (Natural Hydraulic Lime) mortars: Specified by conservation professionals for their breathability and compatibility with historic buildings. NHL 3.5 remains the most commonly specified grade for interior plastering work in 2026, offering the optimal balance between workability and strength

The Enduring Appeal of Lath and Plaster in Contemporary Homes

The resurgence of lath and plaster in modern construction isn’t merely nostalgic – it’s driven by practical advantages that outperform conventional materials. Recent studies indicate that properly installed lath and plaster walls can last over 100 years, significantly outlasting standard drywall installations which typically require replacement or significant repair within 30-50 years. This longevity, combined with superior performance characteristics, makes it an increasingly attractive option for discerning homeowners. A 2025 comparative analysis published in the Chartered Institute of Building journal demonstrated that lifecycle costs for lath and plaster installations were 35% lower than drywall systems over a 75-year assessment period.

Superior Performance Benefits

- Enhanced soundproofing: Up to 60% better sound insulation than standard drywall, according to acoustic testing conducted by The Institute of Acoustics. The mass and multi-layer construction effectively dampens sound transmission, making it ideal for homes in urban environments or properties requiring privacy between rooms. Recent field measurements show sound reduction coefficients (SRC) of 52-58 dB for traditional three-coat lath and plaster systems compared to 35-42 dB for standard 12.5mm plasterboard

- Superior thermal regulation: The thermal mass of plaster helps maintain consistent indoor temperatures, reducing heating and cooling costs by up to 18% compared to lightweight drywall systems, based on 2026 energy monitoring data from homes in Kent and Surrey

- Excellent fire resistance: Lime and gypsum plasters are inherently non-combustible. Traditional lath and plaster typically achieves a 30-60 minute fire rating, exceeding many modern alternatives. Testing by Building Research Establishment confirms that 25mm lime plaster on wooden laths provides 45 minutes of fire protection, meeting requirements for most residential applications

- Greater impact resistance: More durable against daily wear and tear, with a hardness that prevents the denting and puncturing common with drywall. Surface hardness testing shows traditional lime plaster achieves 2.5-3.0 on the Mohs scale after full carbonation, compared to 1.5-2.0 for gypsum-based products

- Breathability: Particularly important in older buildings, lime-based plasters allow moisture vapor to pass through walls, preventing condensation issues and maintaining healthy indoor air quality. Vapor permeability testing demonstrates that NHL-based plasters have μ-values of 5-15, compared to 50-100 for modern gypsum plasterboard, allowing walls to “breathe” and preventing trapped moisture damage

- Moisture buffering capacity: Recent research from The University of Nottingham’s School of Architecture in 2025 showed that lime plaster can absorb and release up to 300g of water per square meter without degradation, naturally regulating indoor humidity levels between 40-60% RH

Aesthetic Advantages

Lath and plaster offers unparalleled flexibility in creating sophisticated architectural features that are difficult or impossible to achieve with modern sheet materials. This versatility makes it an excellent complement to other decorative plastering techniques in high-end residential projects:

- Seamless curved walls and archways: The wet application method allows craftsmen to form complex curves without visible joints. Contemporary architects increasingly specify lath and plaster for organic, flowing interior designs that cannot be replicated with flat sheet materials

- Custom decorative mouldings: Ornate cornicing, ceiling roses, and decorative panels can be run in-situ or applied. Master plasterers can create bespoke designs that match historical precedents or create entirely contemporary interpretations

- Unique textural finishes: From smooth polished surfaces to textured stippled or combed effects. Popular 2026 finishes include troweled leather textures, traditional combed effects, and smooth Marmorino-style polished surfaces

- Traditional period authenticity: Essential for listed buildings and conservation areas where maintaining historical accuracy is required by planning authorities. Historic England guidance emphasizes the importance of matching original plaster composition and application methods

- Integrated architectural details: Niches, reveals, and decorative features can be formed as part of the plaster application, creating seamless transitions that modern construction joints cannot match

- Natural color variations: Lime plaster develops subtle color depth through carbonation, creating luminous surfaces that change appearance with natural light throughout the day – a quality increasingly valued in luxury residential design

Practical Considerations for Modern Implementation

While the benefits of lath and plaster are substantial, it’s essential to understand the practical implications of choosing this method. The installation process requires skilled craftsmen and typically takes longer than conventional drywall installation. Current market data shows installation costs averaging £12-18 per square foot in the UK as of 2026, roughly 45% higher than drywall alternatives. However, when lifecycle costs are considered—including the reduced need for repairs and replacement—lath and plaster often proves more economical over a 50-year period. Data from the RICS Building Cost Information Service indicates that whole-life cost analysis favors traditional plastering for properties expected to remain in service for more than 40 years.

Installation Costs and Timeframes

- Materials: £4-6 per square foot for traditional lime-based systems in 2026; premium materials including specialized aggregates and historic lime putty may cost £7-9 per square foot

- Labour: £8-12 per square foot, reflecting the specialized skills required and the limited number of qualified traditional plasterers available in the UK market

- Installation time: 5-7 days for an average room (4m x 4m), including drying time between coats. Rush jobs that compress curing times typically fail within 3-5 years

- Specialist tools and equipment requirements: Including hawks, trowels, floats, screeds, darby boards, and mixing equipment. Professional-grade tools represent an investment of £800-1,200 for a complete kit

- Additional structural considerations: Lath and plaster adds approximately 20-30 kg per square meter to walls and 25-35 kg per square meter to ceilings, which must be factored into structural calculations, particularly for ceiling applications in older buildings

- Scaffolding and access: Proper access equipment is essential for ceiling work and adds £300-600 to project costs for typical residential rooms

Maintenance and Repairs

Maintaining lath and plaster requires specific knowledge and techniques that differ significantly from modern drywall repair. This specialized knowledge is increasingly valuable for property owners dealing with common plaster cracking issues. According to the Institute of Historic Building Conservation, proper maintenance significantly extends the life of these installations:

- Regular inspection for cracks and moisture damage: Annual checks recommended, particularly after severe weather. Autumn inspections should focus on external walls before winter, while spring checks assess any frost damage

- Professional repair services for significant damage: Matching historic plaster composition requires specialist knowledge. Laboratory analysis of existing plaster (available from conservation specialists at £150-300 per sample) ensures accurate matching of lime type, aggregate size, and binder ratios

- Specialised materials for matching original finishes: Lime putty and appropriate aggregates must be sourced from specialist suppliers such as Mike Wye & Associates or Ty-Mawr Lime, with delivery times of 2-4 weeks for bespoke batches

- Periodic repainting or refinishing as needed: Using breathable paints (such as limewash, milk paint, or mineral paints) that don’t seal the plaster surface. Modern acrylic and vinyl paints should be avoided as they trap moisture and cause delamination

- Addressing underlying structural issues: Cracks often indicate movement in the building structure that must be resolved before cosmetic repairs. Common causes include foundation settlement, timber decay, or roof spread – all requiring structural assessment before plastering work commences

- Moisture monitoring: Using electronic moisture meters (available from £50-200) to detect hidden damp before it causes visible damage. Readings above 20% indicate investigation is needed

Minor hairline cracks (less than 2mm wide) can often be filled using appropriate flexible fillers based on lime putty with fine aggregate, but larger cracks or areas of loose plaster require more extensive repair. In conservation work, the principle of “minimal intervention” guides repair decisions, preserving as much original material as possible. The Building Conservation Directory provides regional listings of qualified specialists experienced in traditional plaster repair.

Environmental Impact and Sustainability

In an era of increasing environmental consciousness, lath and plaster stands out as a surprisingly eco-friendly choice. The materials used are largely natural and recyclable, and the extended lifespan means less waste over time. Studies show that traditional plastering methods have up to 85% lower carbon footprint compared to the manufacturing and disposal of modern drywall systems, according to 2026 lifecycle assessment data published by the Waste and Resources Action Programme.

The environmental credentials of lime-based lath and plaster are particularly impressive. According to research published by the BRE Centre for Innovative Construction Materials, lime plaster actually reabsorbs atmospheric CO2 during the carbonation curing process, partially offsetting the emissions from its production. A 2025 study demonstrated that lime plaster reabsorbs approximately 70-80% of the CO2 released during lime burning, with full carbonation occurring over 1-5 years depending on thickness and environmental conditions. Additionally:

- Natural materials: Lime, sand, and timber are renewable and locally sourced in most regions. UK lime production from quarries in Derbyshire, Somerset, and Yorkshire ensures low transportation emissions for most projects

- Low embodied energy: Traditional lime putty production requires significantly less energy than gypsum plasterboard manufacture – approximately 3.8 MJ/kg for lime plaster compared to 6.2 MJ/kg for plasterboard, based on Institution of Civil Engineers data

- Minimal waste: Mixed plaster can be reclaimed and reused within 24 hours; old plaster can be crushed and returned to soil as an amendment, where it improves soil pH and structure. Lime plaster waste is completely non-toxic and biodegradable

- Durability reduces replacement cycles: A century-long lifespan means reduced material consumption and waste generation over time. Comparative analysis shows that a building lifespan of 100 years requires one lath and plaster installation versus 2-3 complete drywall replacements

- Healthy indoor environment: Lime plaster naturally regulates humidity and is alkaline (pH 12-13), inhibiting mold growth and neutralizing acidic atmospheric pollutants. Clinical studies indicate reduced respiratory issues in buildings with lime plaster compared to sealed drywall systems

- No toxic additives: Unlike modern plasterboard which may contain formaldehyde-based binders and chemical additives, traditional lime plaster contains only natural materials safe for sensitive individuals

For projects pursuing environmental certifications such as BREEAM or Passivhaus, traditional lime plastering can contribute valuable points toward sustainability goals. BREEAM 2026 standards specifically recognize traditional breathable construction as contributing to materials credits (MAT 01) and health and wellbeing criteria (HEA 02).

Making the Choice: Is Lath and Plaster Right for Your Project?

The decision to use lath and plaster should be based on several key factors specific to your project requirements and constraints. When planning significant renovation work, it’s essential to understand comprehensive plastering costs in the context of your overall budget:

- Budget availability for premium materials and skilled labour: Consider both initial outlay and lifecycle costs. Financial modeling over 50-75 years typically shows total cost parity at year 35-40, after which lath and plaster becomes increasingly economical

- Project timeline flexibility: Account for extended installation and curing periods. Projects requiring rapid completion (less than 3 weeks) may not be suitable for traditional methods

- Desired aesthetic outcome: Particularly relevant for period properties or high-end contemporary homes seeking character. Architects increasingly specify traditional plasterwork for luxury developments where tactile quality and visual depth justify the premium

- Long-term property value considerations: Quality traditional plastering can significantly enhance property appeal and resale value. Estate agent data from 2026 shows that authentic period features including original plasterwork command 8-15% premiums in the heritage property market

- Heritage preservation requirements: Listed buildings and conservation areas may require like-for-like replacement of original plasterwork. Grade I and Grade II* properties almost universally require traditional methods

- Building performance priorities: Superior acoustics, thermal performance, or fire resistance may justify the additional investment. Developments near airports, railways, or busy roads particularly benefit from lath and plaster’s superior sound insulation

- Climate and exposure: Lime plaster performs exceptionally well in damp environments where breathability is crucial, making it ideal for coastal properties, buildings near watercourses, or structures with solid stone or brick walls prone to moisture ingress

- Building orientation and solar gain: The thermal mass of plaster provides particular benefits in south-facing rooms subject to overheating, moderating temperature swings by up to 5°C compared to lightweight construction

When Lath and Plaster is Essential

Certain situations make traditional plastering not just preferable but often legally required:

- Grade I and Grade II* listed buildings: Listed building consent typically requires traditional materials and methods. Planning authorities routinely refuse applications proposing modern alternatives in significant heritage buildings

- Conservation areas: Local planning authorities may specify traditional construction methods through Article 4 directions or design guidance. Check with your local planning department before commencing work

- Historic building repairs: Matching existing plasterwork maintains authenticity and building performance. Incompatible repairs using cement-based materials or impermeable systems cause accelerated decay of historic fabric

- Curved or irregular surfaces: Where modern sheet materials cannot achieve the desired form without visible joints or extensive cutting waste. Complex barrel vaults, domed ceilings, and organic architectural forms specifically benefit from traditional plastering methods

- Buildings with solid walls: Structures without cavity construction require breathable internal finishes to manage moisture. Applying impermeable modern plasters to solid masonry walls causes interstitial condensation and decay

- Heritage tourism and historic house museums: Properties open to the public require authentic finishes that withstand scrutiny and meet conservation principles established by bodies like the National Trust

Professional Installation

Finding qualified craftsmen is crucial for successful lath and plaster installation. The pool of skilled traditional plasterers in the UK has declined significantly, with only an estimated 1,200-1,500 practitioners maintaining heritage skills as of 2026 according to Heritage Training Group statistics. Look for:

- Verified experience with traditional plastering techniques: Request examples of previous lath and plaster projects with photographic documentation showing application stages, not just finished results

- Portfolio of completed projects: Including before-and-after photographs demonstrating quality workmanship across different building types and periods. Ask to visit completed projects if possible

- Professional certifications and insurance: Membership in organizations such as the Federation of Master Builders or specialized conservation bodies like the Institute of Historic Building Conservation. Professional indemnity insurance is essential for listed building work

- Strong references from previous clients: Particularly those with similar project requirements. Contact at least three previous clients to discuss their experience, timeline adherence, and long-term performance

- Knowledge of traditional materials: Understanding of lime cycles, aggregate selection, appropriate additives, and regional variations in historic plaster composition. A competent plasterer should be able to discuss NHL grades, putty versus hydraulic lime, and appropriate aggregate types for your specific application

- Understanding of building pathology: Ability to diagnose and address underlying issues before plastering, including moisture problems, structural movement, and timber decay. Good plasterers will refuse to work until these issues are resolved

- Familiarity with current conservation standards: Knowledge of relevant guidance from Historic England, SPAB, and BS 8221 (Code of practice for cleaning and surface repair of buildings)

- Appropriate equipment and mixing facilities: Professional plasterers should have dedicated mixing equipment, clean water sources, and proper storage for materials. Lime putty should be stored in sealed containers and protected from carbonation

For heritage projects, consider plasterers with accreditation from conservation training programs or those registered with The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, which offers specialized courses in traditional building techniques. The Construction Industry Training Board also maintains a register of heritage skills practitioners. Daily rates for qualified traditional plasterers in 2026 range from £250-400 depending on experience and project complexity.

The Future of Traditional Plastering in Modern Construction

The future of lath and plaster looks promising, with industry experts predicting an 18% growth in traditional plastering services over the next five years based on Construction Index market analysis. This growth is driven by increasing appreciation for craftsmanship, sustainability concerns, and the superior performance characteristics of traditional methods.

Several trends are shaping the revival of traditional plastering in 2026:

- Heritage skills programs: Government initiatives and industry apprenticeships are training a new generation of traditional plasterers to address the skills shortage. The Department for Education allocated £12 million in 2025 for heritage construction apprenticeships, resulting in 340 new traditional plastering trainees across England

- Sustainability requirements: Stricter building regulations favoring low-carbon materials benefit traditional lime-based systems. The UK’s commitment to net-zero carbon by 2050 includes increased scrutiny of embodied carbon in construction materials, where lime plaster demonstrates clear advantages

- Wellness considerations: Growing awareness of indoor air quality and natural building materials drives demand for breathable plaster systems. Post-pandemic emphasis on healthy buildings has increased interest in materials that naturally regulate humidity and resist mold

- Hybrid approaches: Architects are increasingly specifying lath and plaster for key areas (entrance halls, principal reception rooms, feature walls) while using modern materials elsewhere, balancing cost with performance. This selective approach allows projects to capture the benefits of traditional plastering within realistic budgets

- Technology integration: Modern tools such as laser levels, digital moisture meters, and thermal imaging cameras complement traditional techniques, improving quality control and diagnostic capabilities. Some practitioners now use photographic documentation and 3D scanning to record application processes for quality assurance

- Research and development: Universities including Bath, Cambridge, and Cardiff are conducting ongoing research into lime technology, developing improved understanding of traditional materials and optimizing formulations for contemporary applications

- Climate adaptation: As the UK experiences increased rainfall and humidity from climate change, the moisture management properties of traditional lime plaster become increasingly valuable. Buildings constructed with breathable materials demonstrate greater resilience to changing weather patterns

- Policy support: Historic England’s 2025 guidance update specifically encourages like-for-like repair using traditional methods, strengthening the case for heritage skills preservation and providing clearer frameworks for listed building consent applications

As modern building techniques continue to evolve, lath and plaster remains a testament to the enduring value of time-tested construction methods, offering a perfect blend of historical charm and practical functionality for contemporary homes. The method’s proven durability, environmental credentials, and superior performance characteristics ensure it will remain relevant for discerning homeowners, conservation professionals, and architects seeking to create buildings of lasting quality. With growing recognition of the limitations of modern lightweight construction and increasing emphasis on sustainability and building performance, lath and plaster represents not just a preservation of heritage skills, but a forward-looking choice for resilient, healthy, and beautiful buildings that will serve future generations.

FAQ

Are lath and plaster walls load bearing?

Lath and plaster walls are often load bearing, particularly in properties built before 1940. An initial assessment involves checking the direction of floor or roof joists above – if they run perpendicular to the wall (crossing it), the wall is likely providing structural support. However, definitive assessment requires professional evaluation. Consult a structural engineer before removing or significantly altering any wall in a period property, as inappropriate removal can cause serious structural damage. The Institution of Structural Engineers recommends professional surveys for all walls in buildings constructed before 1950.

Should I board over a lath and plaster ceiling?

Whether to overboard a lath and plaster ceiling depends on several factors. If the property has listed status or is in a conservation area, planning authorities typically require like-for-like repair to preserve the historic fabric. For non-listed properties, overboarding may be considered if the existing ceiling is significantly deteriorated, but this approach has limitations. The additional weight (typically 10-15 kg/m²) must be verified as acceptable for existing ceiling joists. Furthermore, overboarding conceals services and can make future maintenance difficult. Before proceeding, conduct a thorough survey to map electrical cables, plumbing, and identify any structural issues. In most cases, proper repair of existing lath and plaster proves more cost-effective long-term than overboarding, which often requires complete removal within 20-30 years.

Can you put drywall over plaster lath?

While technically possible to install drywall over lath and plaster, this approach is rarely advisable. The plaster uses the lath for a base until it can dry and harden, forming the visible part of the wall. If you proceed, locating studs is critical – use a stud finder rated for dense materials, as standard detectors may give false readings through plaster. Use screws long enough (typically 50-65mm) to penetrate through both the drywall and plaster to reach the studs securely. However, this method adds 35-45mm to wall thickness, affects door frames and skirting boards, and creates problems at junctions with other surfaces. More significantly, trapping moisture between the old plaster and new drywall can cause condensation and decay. Instead, consider either proper repair of the existing plaster or complete removal and replacement, which provides better long-term results.

Can lath and plaster hold a TV?

You can mount televisions on lath and plaster walls, but proper technique is essential. The key challenge is locating the centre of studs accurately – traditional stud finders often struggle with lath and plaster’s density. Alternative methods include removing a small section of skirting board to visually locate studs, using powerful neodymium magnets to find nails, or carefully drilling exploratory holes. The mount itself is heavy (3-5 kg), and mounting a television creates significant leverage forces that can pull fixings from the wall. Always fix directly into studs using appropriate length screws (75-100mm), never rely on the plaster alone. For particularly valuable televisions or uncertain stud locations, consider hiring a professional installer with experience in period properties. Some specialists offer endoscopic inspection to locate studs without damage. For walls where stud location proves impossible, chimney breast mounting or purpose-built stud work may be preferable alternatives.

When did houses stop using lath and plaster?

In the United Kingdom, lath and plaster remained the standard wall and ceiling construction method until the mid-1950s, with some properties still being built using this technique into the early 1960s. The transition to plasterboard occurred gradually, driven by post-war housing demand and labour shortages. In Canada and the United States, wood lath and plaster remained in use until drywall (the North American term for plasterboard) became widespread in the mid-twentieth century, with most construction switching to drywall by the late 1950s. However, the timeline varied significantly by region, building type, and quality level – high-end properties and custom homes continued using traditional plastering methods well into the 1960s and 1970s. Today, traditional lath and plaster is experiencing a resurgence in heritage conservation work, luxury new builds, and among homeowners seeking superior acoustic and thermal performance.

Sources

[1] https://www.abis.com.au/lath-plaster/

[2] https://mtcopeland.com/blog/what-is-lath-and-plaster/

[3] https://www.thespruce.com/plaster-and-lath-came-before-drywall-1822861